The majority of Irish people have relatives in England, most of whom left Ireland at some point in the twentieth century in an effort to find work. Most of us find ourselves travelling to big urban industrialised areas when we visit the family, but if you are really lucky you have a relative that lives somewhere in the south-west of England, where you can enjoy a summer of cider drinking and funny accents. In the past a large portion of this part of England was called Wessex, named for the Anglo- Saxon Kingdom of the West Saxons. Archaeologists sometimes use the term Wessex as well, to refer to cultural similarities across modern counties in the south and west.

So why the English geography lesson? Well, naturally enough it is all to do with Co. Offaly, and more specifically Bronze Age Tullamore. Situated in the Irish midlands, Offaly may seem a long way from the hallowed apple orchards of Wessex. This does not seem to have been the case in prehistory, however, as we were to discover during excavations one cold wet winter in advance of the N52 Tullamore Bypass, being carried out on behalf of the National Roads Authority and Offaly County Council.

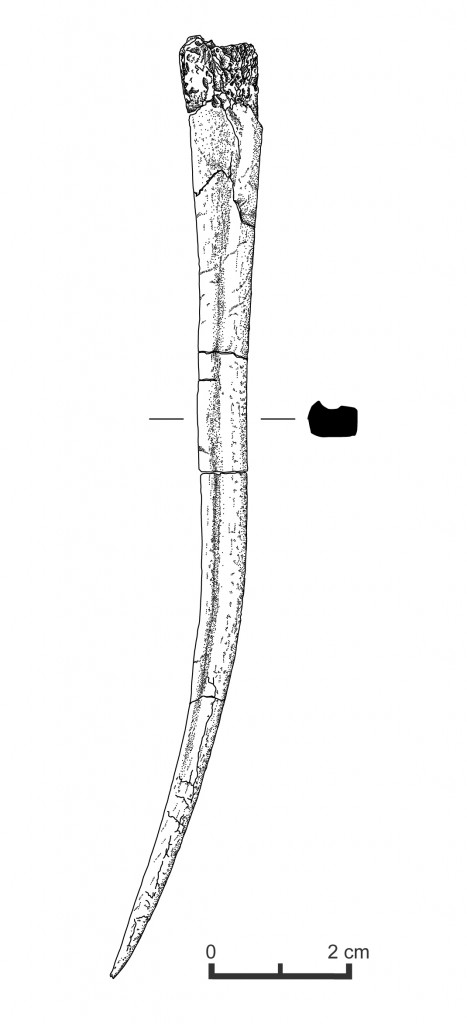

At one of the sites, in the townland of Mucklagh, we discovered an isolated cremation pit, a relatively common feature on an archaeological excavation in Ireland. When these are revealed we collect all the material as a sample so that we can process it later at our office facility, to make sure we don’t miss anything. During the procedure to remove all the bone and plant fragments from the sample we discovered something we don’t normally find in cremations-grave goods. The first artefact to appear turned out to be a small antler awl, a pointed tool probably used for making holes in leather or textiles. However, the greatest excitement came when one bright piece of metal shone out from amongst the other material. This was a small object of what (contrary to popular belief!) is rarely found on an archaeology site- gold.

The post-excavation process began in earnest and our osteoarchaeologists learned that the cremation consisted of two individuals, an adult female and a child aged between 6 and 8. Radiocarbon dating of the remains showed that these people had lived in the Bronze Age (1776-1601 BC cal 2-sig). Our environmental specialists then added further pieces to the jigsaw, examining charcoal fragments which allowed us to ascertain that the main wood on the cremation pyre was oak, with low concentrations of guelder rose also present. Guelder rose is a native Irish tree which tends to like damp shady woodlands. Oak burns at particularly high temperatures and for an extended period, and is commonly recovered from archaeological contexts in Ireland.

As for the gold object, it was sent to the National Museum of Ireland where it was examined by Assistant Keeper Mary Cahill, Ireland’s leading expert on Bronze Age gold. She identified it as a bead cover of Wessex-type, with no known parallels in Ireland. They are most often found in Bronze Age burials in south-west England, with the closest similar finds being a pair of bead-covers from a cremation burial at Barrow Hills, Oxfordshire, and from female Wessex Culture inhumations at Wilsford, Wiltshire.

Paul Mullarkey, of The National Museum of Ireland’s Conservation Department conducted further tests on the gold to discover its composition. It was found to be typical of gold from the period, with over 90% purity and additions of lead and copper. As for the awl, bronze examples have also been found in England, often associated with female burials. A similar bone point was recovered from the cremation burial of a young adult female in the early Bronze Age cist at Poulawack, Co Clare.

So how did the bead cover get from Wessex to Offaly? Was it made in Ireland to copy this prehistoric British tradition or was it traded through many hands between the two islands? Perhaps, as with today, there were links between the people from the two locations, and its presence in Offaly is the result of visits between family and friends. We will never know the real story behind the bead cover and its owners, but it is a fascinating example of cultural exchange in the past, which shows just how close the links were between Ireland and England in prehistory.

This is really interesting. I had heard that in more recent times archaeological gold had traveled in the other direction – from Ireland to Wessex. But I’ve yet to see evidence.