One of the most important roles of any archaeologist is to communicate their findings to others, be they fellow archaeologists or members of the public. The strongest and most direct method of imparting information is by visual means, be it site plans, reconstructions, artefact photography or illustration. Rubicon prides itself on its graphics department, which is one of the largest and most accomplished in Europe. One of the most technical and challenging aspects of archaeological graphics is artefact illustration, a technique discussed by AAI&S board member and Rubicon Illustrator Sara Nylund.

The archaeological profession and its sub discipline of archaeological illustration have seen astonishing leaps in technology over the last number of years. The realm of archaeological graphics is now dominated by the computer, on which the vast majority of work from the site plan to 3-D flythrough takes place. One could easily be led to believe that all the traditional methods of recording finds are being replaced with new techniques. Yet even though new, sometimes mindboggling technologies are available, archaeologists turn to one traditional method time and time again for a record of their finds – Artefact illustration.

Artefact illustration – just a pretty finds drawing?

So what is an artefact illustration when it really comes down to it, and why has it not been replaced with 3-D scanning or a straightforward photograph? Surely the first would give much more information on the object and in a 3-D environment to boot, and the second would represent a huge saving in both time and expense?

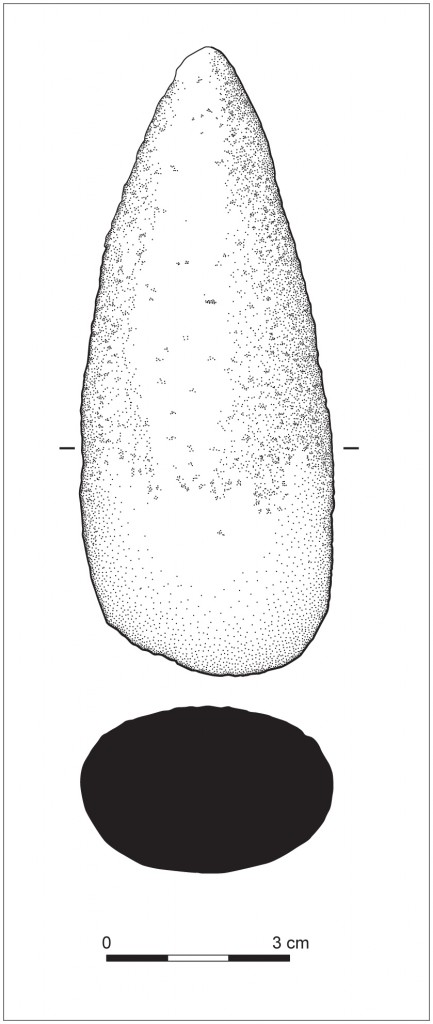

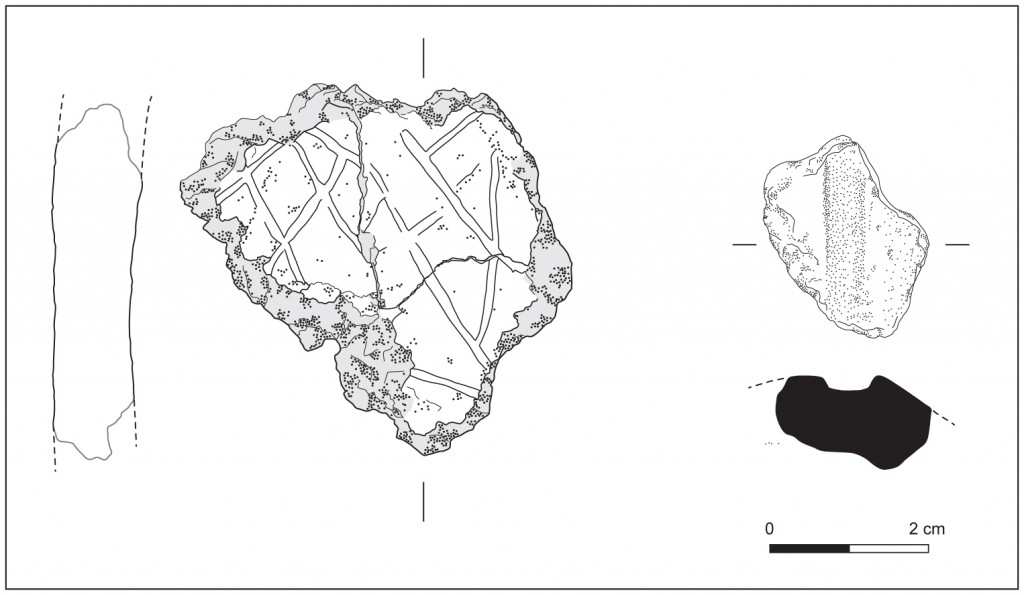

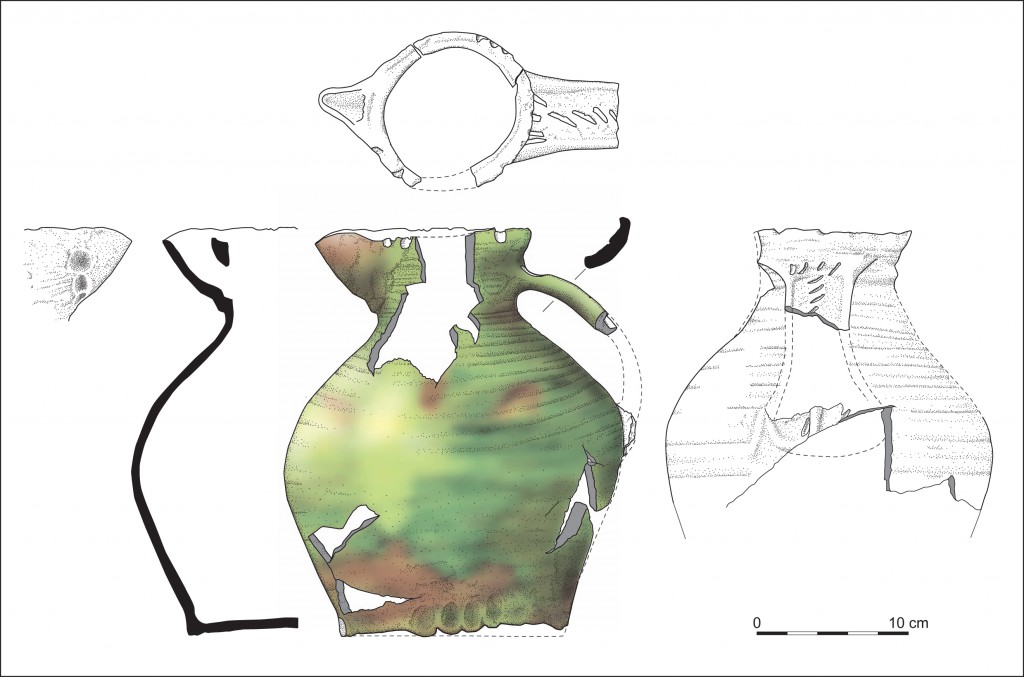

Ultimately it all comes down to one thing, the trained illustrator´s ability to interpret the object requiring drawing. The purpose of an artefact illustration is to act as a true record of the object and its material condition, to show any diagnostic features and manufacturing techniques present. A drawing of this type is interpretative; it contains information on size, shape, decoration, manufacturing techniques, thickness and appearance of fabric, and shape in section. To achieve this, artefact illustrations often contain several views as well as sections and projections of the artefact. Finally, the finished illustration must convey to the viewer any aesthetic qualities inherent in the object.

This is why a scanner or camera cannot replace the illustrator. These techniques will document the find “objectively” (however, most digital software and hardware have inherent problems which although viewed as producing objective and precise reproductions will introduce misinformation or distortions, but these are a topic for another day).

When reviewing a finds illustration, here are some straightforward guidelines in recognizing a good artefactual drawing. The general layout of the drawing will be set out in an organised and logical manner, and the drawing will be clean and tidy in appearance. The light source is always placed in the upper left hand corner, and the main view of the artefact is depicted straight on, with accompanying secondary and section views (generally at a 90° angle to each other). Depending on the type of find, the illustration will be rendered in different ways using stippling and lines where appropriate. Finally the illustration should show original features as clearly distinguished from damaged areas.

Archaeology will always require illustrators who can produce a visual record suitable for publication of the finds uncovered. Artefactual drawing requires a more scientific approach than a pictorial study would, while still demanding the same skills required from a traditional artist. In this, computers have yet to replace the human touch. But then again who knows what the future will bring?

Pingback: Fundillustrationen in das digitale Zeitalter | Alpine Archäologie

Pingback: Kreslit, ci nekreslit? Tot otázka! « MONUDET

I’ve always wondered why they still draw the findings on site, while in the ground? Because they always take photos as well. I can understand before digital cameras there was never a guarantee the photos would come out, but with digital cameras now, previews of what you’ve taken, what is the reason to still sketch out the findings as they appear in the ground?

Hi Jon, are you referring to artefacts being drawn while still in the ground? I can say that I would rarely see that happen unless there was some importance to the location or placement of the artefacts, most finds tend to be incidental within their contexts. Articulated skeletal remains are an example where a detailed and scaled drawing would be made before they are removed. Several reasons; you never know whats going to happen to your camera or digital archive between the time you use it on site and the time you get back to a base office and back up all the information. A drawing provides a scaled image looking directly down at the subject, unlike a photograph which is usually taken from a standing person’s perspective which is generally going to be from an oblique angle which is not of much use for research. Colour, lighting and shadow are major issues when taking photographs in the field-archaeology is not professional photography obviously and you wouldn’t have all day to set up the perfect lighting conditions for a photograph. Sometimes a whopping great shadow is cast over half your subject with the other half glowing brightly in the sun, most of the time though there is a pool of water in your trench-either way soil conditions alone are most often indeterminable from a photograph. Subtleties such as a grave cut which is as clear as day to your eyes when standing looking at it-are just not visible when you go back to the office and trawl through your photographs. Drawing on site works around all this and provides a far more detailed record than a photograph in most cases. Once a site is excavated and everything back filled-that is it-no going back to check something you forgot to write down, exactly how close subject A was to subject B-from a scale illustration real measurements can be taken, sometimes with millimetre accuracy-from a photograph its vitually hopeless due to the angles and lack of proper scale. Written notes and context information pretty much always accompany an on site illustration. This includes labelling of layers and artefacts which, with a photograph can only be done at a later stage (sometimes at a much later stage after digging several other sites) Imaging trying to piece together a story from hundreds of photographs of different patches of soil or eighty skeletons, even if you were really dilligent and placed labels beside everything before photgraphing, chances are half these labels turn out to be illegible when you look at them on screen. In short-its so important to have as detailed an archive as possible prior to leaving a site each day. Unfortunately, for all the great advancements of photography it still falls somewhat short of a good collection of decent scale drawings. Hope that clears things up a little?