Late last week our osteoarchaeologist Carmelita Troy made a gruesome discovery amongst an otherwise unremarkable post medieval skeletal assemblage. One of the individuals displayed signs on her remains that she had been suffering from the advanced stages of a serious infectious disease, an ailment which had a particularly destructive impact on her skeleton. Further analysis revealed that prior to death the unfortunate woman had been enduring the advanced stages of what is sometimes called ‘Cupid’s Disease’- syphilis.

Syphilis is a bacterial infection that is transmitted through sexual contact, also known as acquired (venereal) syphilis. Infected mothers with the disease can pass it to their developing foetus in the womb, and this is called congenital syphilis. The origins of the disease remain unclear; one theory suggests that Columbus and his crew transported the disease to Europe on their return from the New World in AD 1492 (Old World versus New World hypotheses).

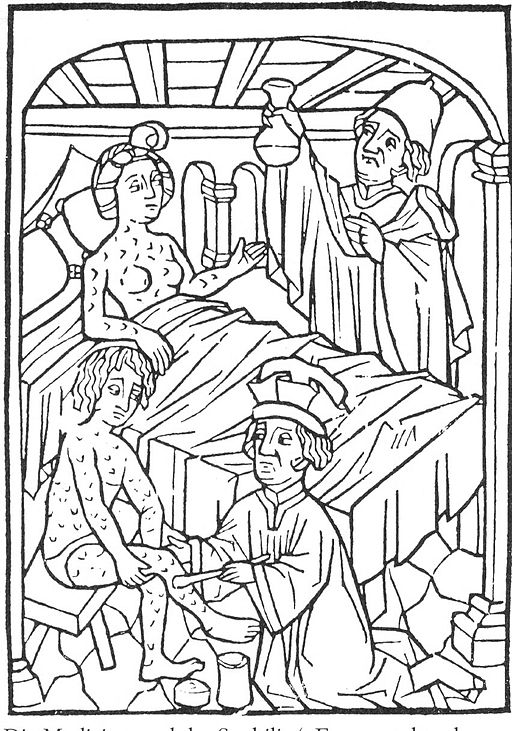

Syphilis has three stages of infection. Primary syphilis includes painless lesions at the site of infection and may go unnoticed, especially if these lesions are located inside the body. The secondary infection sees a rash form on the skin, and other symptoms may include fever, fatigue, aches and pains. The bacteria are then later transported to the site of tertiary infection in the bone via the bloodstream. It is only in its advanced stage that syphilis affects the skeletal structure, as well as causing problems to the heart, brain and nervous system, resulting in attacks of irrational madness.

The pitting visible on the bone is a result of erosive lesions which are followed by new bone being laid down as the body tries to heal itself. In archaeological terms, the presence of the cranial vault scars, termed caries sicca, is important for the diagnosis of acquired syphilis, since they are characteristic of this disease.

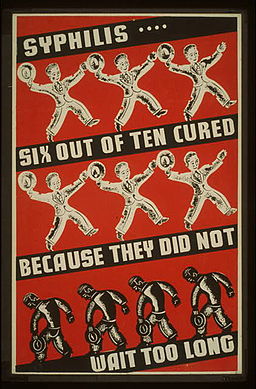

Today, syphilis is easily cured if it is treated with antibiotics (penicillin). Unfortunately for our late and post medieval ancestors this treatment was not an option, and as with this woman, their contraction of syphilis proved fatal.