A 12th-century motte castle was the subject of a challenging topographical and geophysical survey that was recently conducted by Rubicon Heritage Services within the policies of Cally Palace near Gatehouse of Fleet, Galloway, in south-west Scotland. The work was undertaken for the Forestry Commission Scotland in what was a truly beautiful setting. Rubicon surveyor Enda O’Flaherty fills us in on the details…

Motte castles can be described as a flat-topped earthen mound whose summit would have originally carried timber buildings and defences. This settlement form was initially introduced into Scotland in the early 12th century, with the greatest concentrations found in Galloway where the feudal system was first introduced. During the early 12th century, Galloway represented a separate kingdom in the south-west of Scotland. In 1124, David I invited Norman nobles to Scotland to help quell the rebellious chiefs of Galloway. It was during this period that these frontier settlements were constructed in the region. Towards the end of the 12th century, many of those Normans who had settled in the area during the preceding decades, and the settlement sites they had constructed, became the focus of local disputes and hostilities, with many motte castles being destroyed during this time.

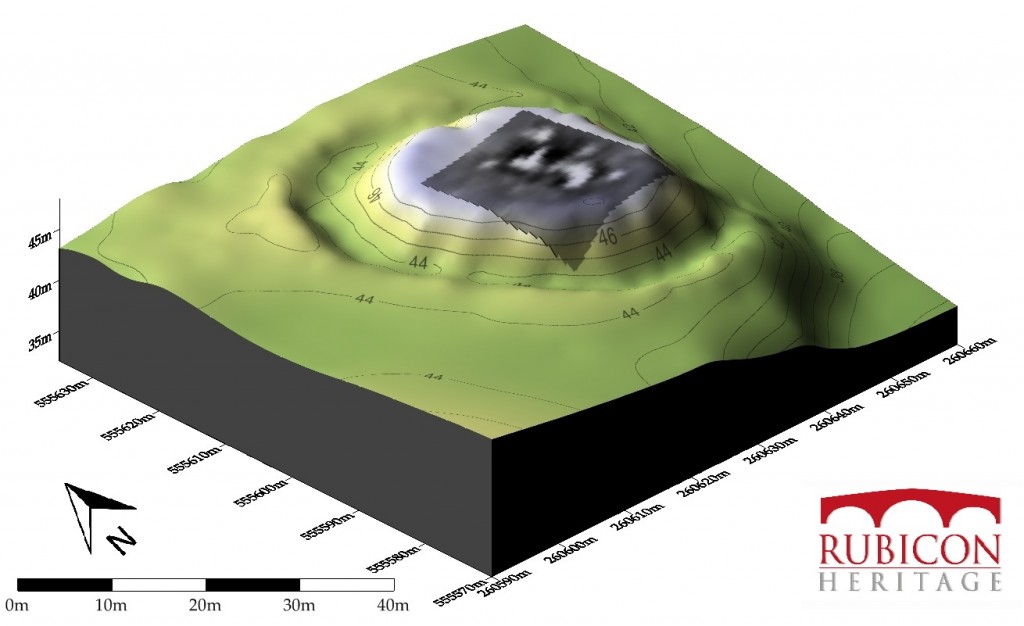

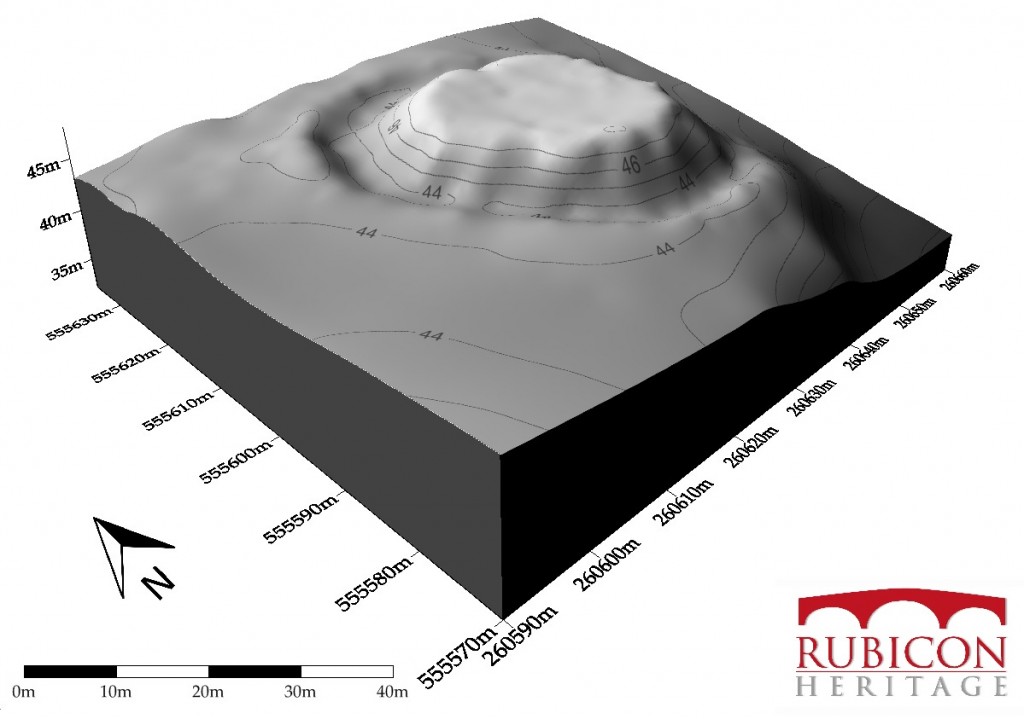

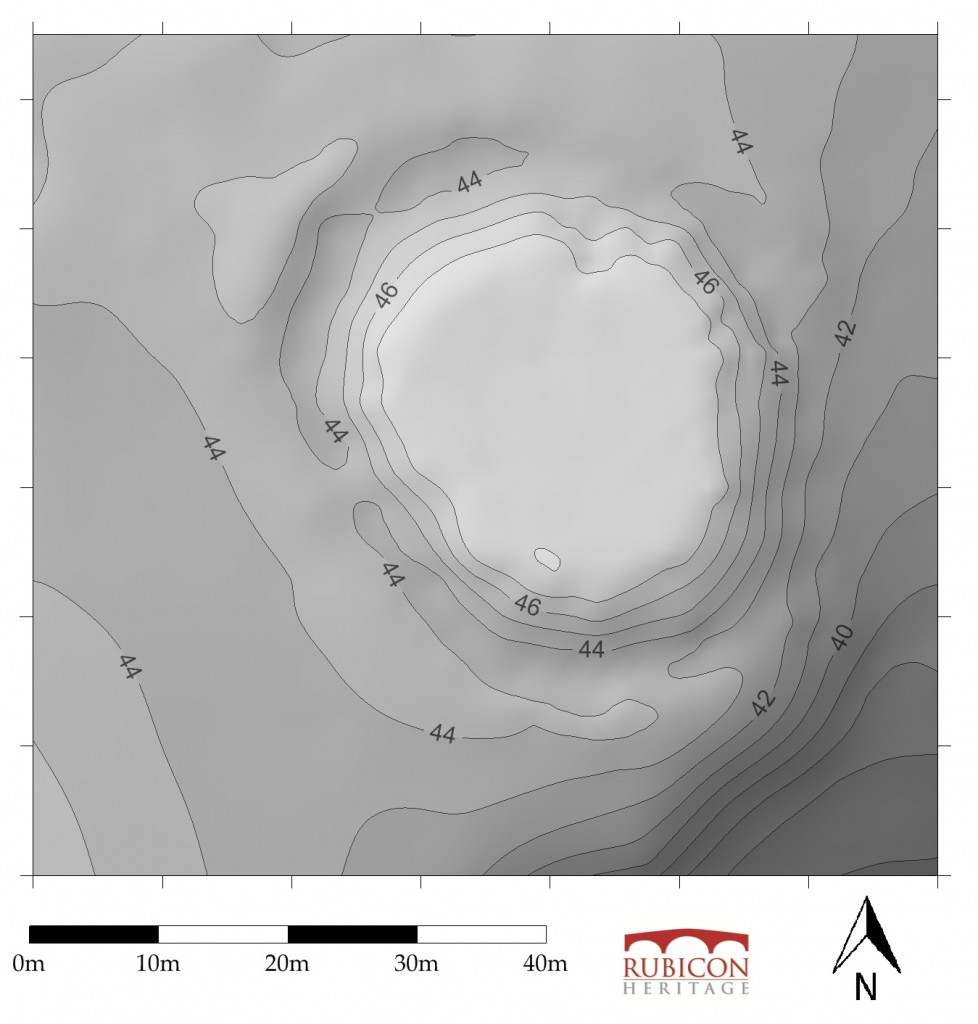

The site comprises a well-preserved earthen mound situated in the undulating mixed woodlands of Cally Palace. The dense woodlands that are encroaching on the site today, presented a challenge for our survey team whose aims were to record the nature and extent of the archaeological features at Moat Park motte, and to provide information which could be used in the conservation and management plan for the monument. A series of geophysical surveys were also conducted on the summit of the mound to identify possible buried features at the site.

The topographical survey of Moat Park motte demonstrated that this site was constructed by cutting a substantial ditch around the summit of a low ridge which occupied a strategic position on the landscape. It was clear that the natural topography was utilised to create a defendable earth and timber castle. Defensive earthworks such as the counter-scarp on the southern and western sides may have carried other defensive features such as a wooden palisade.

The results of the geophysical survey suggested that the summit of the mound was occupied by some structural features. The electrical resistivity survey did not reveal evidence for substantial ditches or walling on the summit of the mound. However, given that motte castles were most commonly constructed of earth and timber, it is not surprising that no substantial structures were detected on the summit of the mound by this survey method. Nonetheless, the results of the fluxgate magnetometry survey identified subsurface magnetic anomalies associated with human activity on the mound.

Areas of high-magnetic responses can be associated with substantial structural features such as masonry walls, or substantial ditches. However, as we know, such features are not common in 12th century motte castles. Another explanation of this magnetic response may be an episode of burning at this location which would be easily detected by the fluxgate magnetometer. The irregular form and substantial size of the area suggested that this magnetic response does not represent a hearth and may perhaps be associated with a once-off conflagration event. Given that the majority of mottes supported substantial timber buildings, similar in dimension to the anomaly identified during the fluxgate magnetometry survey, and also the historical evidence for turbulent events involving those Normans who settled in south-west Scotland during the 12th century, it is plausible to consider that the timber buildings which once stood on the summit of Moat Park motte may have been destroyed by fire.